Art Stories

Tales of inspiration and creativity, behind-the-scenes glimpses at art-making, in-depth arts features, and narrative portraits of LAL artists.

A New York-based artist currently participating in More Art’s 2015 Engaging Artists program, Chee Wang Ng doesn't let location or multiple projects slow him down. "We are all focused on working 24/7—a constant. Sleep is overrated and another show is done,” Ng says. In the past few years, Ng explored different mediums for various exhibitions that Lexington Art League (LAL) showcased. He displayed his video "108 Global Rice Bowls”, and for SITE, he presented a walk-in labyrinth entitled "The Three Hundred and Sixty Walks of Life Labyrinth". For Ng, FEAST: Pleasure + Hunger + Ritual opened at just the right time, and he had the perfect piece for it. “I had just finished writing the proposal for ‘In The Name of Our Forefathers - Clear Tea Light Rice’, and LAL was looking for work with food as the theme of the show. It was not created with any particular site in mind. When Becky Alley, curator, chose it for FEAST, I sort of thought that it might work in LAL's long hallway. It turned out to fit so well,” Ng says. “In The Name of Our Forefathers - Clear Tea Light Rice” involves the hanging of 60 cow creamers of different origins and time periods in order to represent the deplorable discrimination that Chinese migrants faced from the 1800s and on. Western nations such as Spain, France, England, and the United States enslaved, lynched, and trafficked in Chinese migrants. Ng utilizes this piece as a chance to inform his audience of the appalling treatment Chinese people faced during this time, and as a result, are still recovering from. “We all share the same human value and dignity and seek the same social equality of a just and progressive society,” Ng says. Even though Ng wasn't able to be present for the opening of the exhibition because of his artist residency program, he was still able to view pictures from the night. “It was most interesting seeing the audience interacting with the cow creamer. This would not be my first installation where the audience just could not help themselves. My work is very interactive and sort of invites the audience members to play with it,” Ng says. Ng takes advantage of the interactive aspect of his artwork by making sure each piece carries a theme that his audience can identify with. "As much as my work is about self-identity, it is also about reaching out and relating to people. This may seem simple, but it is packed with the complexities of layers upon layers of narratives. A certain visual vocabulary runs through all the various mediums in my work, I let the medium carry the message,” Ng says. Unfortunately, as many artists soon find out, not everyone will understand the message behind a particular work. Ng takes it all in stride, though. "I can present my work in a certain way, and the audience will still have other ways to perceive it—the beauty of contemporary art,” Ng says. Sometimes, the original intention behind the creation of a new project evolves, and Ng is left with a surprising but welcomed finished project. "I structure my work for the clarity but the magic is when the work goes beyond my original thought—the unexpected, the chance encounter, the moment of creation in which all these parts just come together. A prime example would be this cow creamer garland—now that it is done, all the different elements fit together so well but for the longest time, I could not explain nor express this ‘cow sense’ to anybody, but when it is done, you see how simple and logical all these are interlinked—like our lives,” Ng says. This isn't the last time people will see "The Name of Our Forefathers - Clear Tea Light Rice". Ng is already on the move to showcase his art at other institutions. "As an artist, you always build upon your older work. I am lucky to have already been booked for a few other shows in which I will improve upon this and also adjust and adapt to each new site,” Ng says. While he's having his artwork featured at different exhibitions, he is also starting on a new project. "I am already deep in structuring a new project in my art residency which I am pretty excited about—working with seniors but still within my discourse,” Ng says. Ng has his own advice for aspiring, young artists seeking to reach the level of success and influence that his artwork has: "Life is art making, never stop."

0 Comments

The Woodland Art Fair presented by Nancy Barron and Nancy Barron & Associates has become a staple event for Lexington in the summer. This year marks the 40th anniversary of celebrating 200 artists along with live music, food, and community activities. Beginning in 2013, a new tradition was added to the fair: The Big Tent.

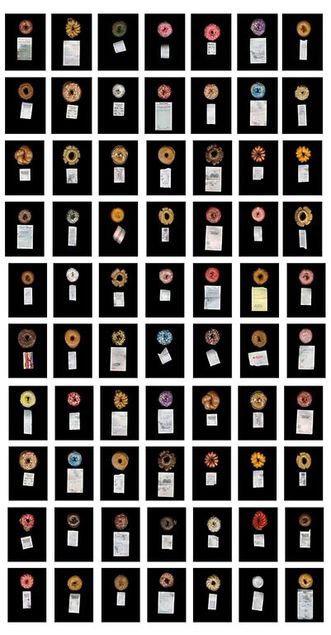

The Big Tent is a one-of-a-kind experience for local artists that have yet to be introduced into the Woodland Art Fair. Each year, four artists are selected to participate in the “Big Tent.” We, at the Lexington Art League, choose artists that would be a good fit for the fair and would greatly benefit from this learning opportunity. These artists are given the chance to sell their individual work without paying the application or booth fees; they are also omitted from the jury process and ineligible for awards. In the past, Big Tent Artists have included: Elizabeth Foley, Sarah Heller, Darrell Kincer, Margaret and Josh Smith at Dovetail, Daniel Graham, Rachel Elliot, Cricket Press, and Lennon Michalski. Some of these artists enjoyed their experience as a Big Tent Artist in the past and have applied to be artists featured at this years Woodland Art Fair. You can also find some of these artists on our website or at the Community Supported Art (CSA) Shop. The Woodland Art Fair never has a shortage of talent and the Big Tent is no exception. The Artists chosen for the 2015 Big Tent are: Matthew Cook of Borderstate, Dronex Inc, David Kenton Kring, and Sarah Jane Sanders. Matthew Cook began his company, Borderstate Made, right here in Lexington, Kentucky. Each piece is individually crafted by hand using materials specifically selected for wear and tear. When an item has reached completion, a six-digit number is stamped on the piece to reflect the date, a guarantee of durability and longevity. If you’ve taken a stroll through Lexington before, you may recognize this group of artists featured in the Big Tent this year. Dronex Inc is an artist collective that was founded in 2004. Their work hopes to inspire a wide range of audiences to recognize and embrace the absurdity in our reality. Whether in a gallery or on the side of a building, the artists of Dronex Inc take advantage of providing art in any surrounding. Lexington resident David Kenton Kring works with ceramics and mixed media. Kring fell in love with creating by hand when studying at Transylvania University. He often uses dark humor and storytelling in his figures. Kring takes advantage of a wide range of human emotions through facial expressions in his work. His goal is to portray a deeper connection with the viewer through narratives. Finally, we have Sarah Jane Sanders. She is a local food and editorial photographer and is currently featured at the Loudoun House as a part of the FEAST: Pleasure + Ritual + Hunger Exhibit. After being mentored by a local photographer, Sanders began to understand her strengths as a visual artist through the lens. Her style is simplistic, natural, and will probably have your mouth watering. Visit each of these artists at the 40th Anniversary of the Woodland Art Fair presented by Nancy Barron and Nancy Barron & Associates in the Big Tent located in the central-most part of the park on Saturday August 15th and Sunday August 16th.  Los Angeles based artist Andrew Pasquella utilizes bold clean lines and vivid colors pay that homage to a pop art aesthetic while grabbing viewer attention with propaganda-esque text and symbols in his USDA Series. During a career working alongside the U.S Department of Agriculture, Pasquella gained invaluable first-hand insight concerning food policy and advocacy to influence his work as an artist. Pasquella’s experience with the USDA has allowed him to formulate a critical assessment of the food industry and its oftentimes negative effects on consumers. Employing the recognizable and controversial USDA organic logo, Pasquella’s USDA Series challenges viewers to take on a more censorious attitude when thinking about issues related to the food that we eat. How are we manipulated as consumers? Who can we trust with our food? Am I educated about products I consume? Can we rely on government organizations to act with integrity? USDA Series calls forth these questions and countless others. We contacted Pasquella to learn more about his USDA Series currently on display here at Lexington Art League. Lexington Art League (LAL): What choices or influences in your life have led you to pursue a career as an artist? Andrew Pasquella: I come from a creative family. My father has his MFA and grew up with the likes of Ed Ruscha in OK, my mother was an amazing landscape architect and photographer and my brother is a talented, published, author. Creativity was abound but it wasn’t until I had gone through a career working in the health, wellness and food industry and witnessing things in those industries I wanted confront that I turned to art full-time as a way to contribute to the conversations circling those industries. LAL: What first got you interested in making art about food issues and policy? AP: Part of my job duties was working closely with the USDA to maintain organic certifications. The more I learned about the USDA, not to mention personally witnessed, the more conflicted and angry I got. The illusion of what I believed “organic” to be fell away to the realities of corporate interests and politics. LAL: What is it specifically about the image of the USDA “organic” certification label that inspired you to use it in the work? AP: Because my personal experience was specifically in the organic world, the logo seemed like a no brainer as a starting point. It’s also a recognizable symbol so when it’s transformed into something else you have the immediate understanding of what it is derived from and you can take the viewer on a journey depending on how you’re transforming it. LAL: Anything specifically that inspired this work and your other work? AP: The canon of pop art. LAL: I have heard only a little about how misleading USDA Organic labels can be and how it is really difficult for consumers to know what is actually in their food. Could you explain a bit more about the controversies addressed in your work? AP: My issue with the USDA organic program is that it began as a way to help prop-up a cottage industry of mom and pop growers and retailers but quickly began to shift as soon as large food corporations saw that they could charge 40% more by simply calling something organic. These entities moved in large amounts of lobbying money and power to change what the organic standards once were to better fit their manufacturing processes and ingredients they could use to make the end product cheaper yielding more profit for them. Now more chemicals, additives, preservatives are allowed into the organic food chain that were never intended to be there and every year more are presented to the USDA for approval. Keep in mind this is a government agency that has a board and employees made up of ex-employees of the same companies proposing new ingredients and rules. LAL: What kinds of research have you done regarding the food industry, animal rights, environmental policies, USDA standards, etc.? AP: I had a ten year career within this world so that entailed lots of reading of a variety of materials, learning the actual organic programming standards, hearing stores, seeing things first hand. LAL: How and why do you choose the words that accompany the USDA? (i.e Politic, Sadistic, etc..) AP: I enjoy using text in much of my work. For an English speaker the written word is instantly recognizable however the context that work is used is where the transformation and journey can occur. The goal of the “word pops” for each piece is to hook the viewer by them acknowledging that word but then observing how that word is used in the context of the organic logo and what that might mean when taken as a whole. I generally like to use words that “dirty” it up a little. LAL: The craftsmanship of your work is impressive! I’ve noticed from other works on your website that your style is fairly minimal with really crisp lines and colors. How does this aesthetic contribute to the work? AP: Thank you! I personally am attracted to a clean modern aesthetic and sometimes that’s all I need as a jumping off part. The bold and graphic nature of my work is certainly mean to be easily digestible yet loud but at the end of the day I’m fully aware that my collectors and buyers want to hang this in their home and while I don’t make art to match curtains or sofas, if I wouldn’t want to look at something I created in my home then I’m not going to make it. LAL: Any advice for consumers? AP: My biggest advice to consumers (so… everyone) is to educate yourself. The biggest mistake you can me is walk around with blinders on thinking government or corporate entities have your best interest in mind. They don’t. Start asking questions and question everything. There’s a world of education out there, find sources that you can trust. LAL: The show at LAL is titled FEAST: Pleasure + Hunger + Ritual – If you could put your USDA Series in one of the categories (pleasure, hunger, or ritual) which would it be and why? AP: Those are all the same thing for me. Food lends itself to all of those and my series aims to question food. The issues around food, not just political, but psychological, physiological and spiritual should all be addressed as a whole. I believe we too often like to use the reductionist approach to try to pick things apart allowing the more important aspects to be lost in the details. Check out more of Pasquella’s work on his website http://andrewpasquella.com/ USDA Series by Andrew Pasquella  Donuts of Long Beach, CA by Rebecca Sittler Donuts of Long Beach, CA by Rebecca Sittler Long Beach, CA based artist Rebecca Sittler transforms and elevates the humble donut to an object worthy of contemplation and examination. For her piece Donuts of Long Beach, featured in LAL’s current show FEAST, Sittler visited every known, independently owned donut shop in Long Beach, CA with “donut” in the title. A plain glazed donut was purchased with a specialty donut and both were documented by placing the objects and receipts on a flatbed scanner in a darkened room. Attached to the wall with map pins, the photographs suggest something more than a delicacy. Despite their ability to make the viewer desirous, the donuts manage to also elicit a reaction beyond visceral hunger. The “gem-like” confections make viewers consider the ways in which we explore, discover, and map our worlds through food. Sittler is both photographer and collector and each donut specimen gathered narrates a journey led through the exchanging of goods. To find out more about Donuts of Long Beach we contacted Sittler and interviewed her. Lexington Art League (LAL): What is your background as an artist? What choices or influences in your life have led you to pursue this career? Did you always know you wanted to be a photographer? Rebecca Sittler: No not at all, I didn’t know. The first time I was exposed to photography was in high school. My art teacher brought in a photographer to do this workshop with us- I just really loved it. I thought “Oh this is great – I’ll probably keep doing this.” It was the first time I really found something that I wanted to do with art. I always had liked art but I never thought it was a realistic option for me. But I went to college for actuarial science- I was very good at calculus – I liked the idea of doing something with math. I had to take some electives in art and English but I wasn’t focused on it. I actually made my dorm room into a dark room- My dad found an enlarger for me and all the stuff I needed. I guess I wasn’t thinking about all those chemicals in my room! Still it was not something I was considering for a career yet. After a full year of being in college I decided I needed to take a step back from the actuarial science degree. I instead went to University of Nebraska, Lincoln and I took some art and English classes over the summer where I really fell in love with photography so I became an art and English major. I was lucky to have some really great professors that talked about how images can function in the world and how they could be analytic and poetic at the same time. I love being in the dark room. I love talking about pictures. LAL: How did you go about researching/ finding these donut shops? Did you make a list/schedule and decide which to go to? RS: Well I moved to Long Beach with my husband from Orlando where I taught at the University of Central Florida. I had only been to California one other time when I interviewed for the job so I was really unfamiliar with Long Beach. I sort of used the donuts as a way to map out my new surroundings. It was like an intro to Long Beach. I went to practically every neighborhood seeking out these donut shops. It was a strange way of mapping my new home, learning about it, and being open to it. I found it humorous how there was this huge Dunkin Donuts “following” at Mass Art where I got my M.F.A. and in Orlando too. It struck me as unusual that these independent donut shops were really iconic in southern California. I was so interested in these independently owned shops. My dad had been a small business owner maybe that is part of the reason why I liked them. The work I was making at the time I moved to Long Beach was centered on American fast food culture so I thought the donuts could be an interesting extension of that. I also have this idea where I like to get out of the house when I’m photographing –I like to be adventurous and just be out in the world. I would map them all out usually and make a list. In my head I would try to kind of catalog these donut shops. So I would hit an area of town and hit like 6 or so at a time. I would try to get 5 or 6 donuts and then I would take them back to the scanner. I documented about a year maybe – my first year in long beach. Since I work I would just take a week and conquer one side of Long Beach – I would try to do it in my free time. The dates aren’t necessarily important and I wasn’t being too methodical. LAL: The way you approach documenting the donuts is somewhat scientific which is kind of counter-intuitive to the way people approach donut eating (nobody seems to think critically about their donut!). Why did you choose to present them so methodically? RS: I think that the donut is so much more interesting when it is looked at as an object and when it is separated from just being something delicious to eat. Food takes on a personality. A lot of people would look at a photo of a donut and say something like “that makes me hungry” but I want it to go beyond that. With the donuts I was thinking: What is the function of this thing I’m photographing? How can something represent itself but also be an idea? What are the relationships between objects that make you feel an emotion other than hunger? I like making things “non-edible.” I’m thinking about them like characters in a drama or sculptural objects. We have this desire to consume donuts and Americans understand them – I wanted to reconcile that with this idea of mapping – by showing where they came from it becomes more than a donut- it’s represents community, a place, a sensibility, a relationship. The receipts are also like little traces of the places I explored. I didn’t want the donuts to be just eye candy. I wanted to introduce something more analytical – I was like a scientist writing in new location and taking samples, however it’s not just a record of donuts I ate. Usually by the time I got a few the whole car was smelling like sugar – I wouldn’t always eat them especially after I messed around with them on the scanner! LAL: Anything interesting you learned through your research and exploration? RS: It was interesting for me to see that some of these independent shops were taking a similar approach to the corporate business model. I wanted to know: What does it mean to be an independent shop in an age where people like familiarity in their food? I was curious how this competition of large donut corporations affected these shops. Something else interesting was that, as it turns out, the majority of the donut shops in Long Beach were started by Cambodian families. All these refugees came to Southern California to escape their government and genocide in the country. Other family members would learn the trade and it would spread through the community and new generations would learn the trade and pass it down. I could sense that there was a community between these shops- they were sharing ideas and business models. I thought about how surreal it must be to come to California after enduring a terrible war- I found that fascinating – Sometimes the research takes you somewhere unexpected. LAL: Your style is fairly minimal in content and the focus seems to really be on specific objects. What has drawn you to object photography? RS: I’m kind of an analytical person. I’ve always used objects to think about things that are not objects. I can give personality to the objects – I use them to work out human relationships – I’ve photographed people but I’ve found that I like spending time with the objects more. They can take on a set of projections. I can change them. I can’t take over when I’m taking a picture of a person. With a picture of a person, it was more about them rather than me bringing something to the photograph. With objects it was always more my voice. The distance helps me feel like I’m participating more in making the picture. LAL: Why use a flatbed scanner and not just your camera? RS: I just like the way it looks. It lights the object on all sides and gives it a glow. I actually really wrecked the scanner with the donuts, I sometimes like to do things that seem counter intuitive. It also made them seem more like objects you can touch; these little gem-like things. They reminded me of photo grams from the darkroom and I liked that too. LAL: The show at LAL is titled Feast: Pleasure+ Hunger + Ritual. Which category (pleasure, hunger, or ritual) would you put your piece under and why? RS: Probably between pleasure and ritual – I was trying to get myself out of my comfort zone- It was an excuse to go somewhere and see things and I had a specific goal. I had to talk to people and explore places I haven’t seen so in a way this was a ritual for me. But there was also pleasure of being out in the world and having a goal that brought me there and seeing these places and individuals. I was operating on a “collector” mentality. LAL: What advice would you give to new artists/photographers? RS: The idea of never forgetting to follow your curiosity has been very important to me. If you give it time, if you are dedicated, your photography changes as you grow- It can give you access to things that are really incredible and it can teach you about yourself and the world continuously. I’ve found that the medium of photography always rewards curiosity. See more of Sittler’s work on her website: http://www.rebeccasittler.com/  Self Service by Kenneth Eric Adams Self Service by Kenneth Eric Adams Artist Kenneth Eric Adams, currently pursuing a Master of Fine Arts from the University of South Carolina, is exploring the complexities and controversies surrounding refined sugar for his thesis research. His works Pile and Self-Service are currently featured in our present show at Lexington Art League, FEAST: Pleasure + Hunger + Ritual. The simple aesthetic and minimalist presence of Adams work allows the viewer to get right to the point of the content: sugar and its overwhelming existence in our daily lives. Both presently and historically contentious, sugar production and consumption has had an undeniably negative affect on the health of consumers. Adams utilizes scale to unnerve the viewer with a sickening amount of sugar while retaining a relatable familiarity with found objects and commonplace materials. Instead of being hidden behind the guise of advertisement manipulation, the sugar in Adams’ work is completely exposed, stripped down, and separated from its societal connotations with pleasure for the viewer to scrutinize and dissect. We wanted to know more about the ideas surrounding Pile and Self-Service so we contacted Adams to gain further insight. Lexington Art League (LAL): What is your background as an artist? What choices or influences in your life have led you to pursue this career? Kenneth Eric Adams: I started taking drafting classes in high school. When these classes were canceled, I was directed to the art department. I earned a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts from Jacksonville University in Jacksonville, FL in 2010 and I am currently pursuing my Master of Fine Art’s degree from the University of South Carolina in Columbia, SC. I have always enjoyed working with my hands and building things, art has allows me to continue these passions while teaching others new skills as well. LAL: What are your motives for making art? KEA: I make art to help me understand and articulate my frustrations with modern life. Expressing my thoughts visually allows me to communicate ideas, which I could not convey as successfully any other way. LAL: What first led you to pursue a work that was inspired by an aspect of commercial food production? Is this theme reflected in other work that you make? What other concepts are you interested in? KEA: During a class in my first year of graduate school, my professor asked our class what issues we thought would be the most important for the future of our civilization. After the group exchanged answers, he quickly turned and said, “Why aren’t any of you making work about these topics.” A few years prior, my wife and I made drastic changes to our own diets and began to research and learn about processed foods, organics and local food movements. I wanted to make work about something I understood or had experienced myself. I am currently creating a new body of work for my thesis based on sugar that will be similar to the works in the exhibition. LAL: What was the process for creating Pile and Self Service, from idea generation to production? (Do you ever stick to a schedule when creating work? Will you work on multiple pieces at one time? How do you know when it’s “finished”?) KEA: My process for creating is broken into two main stages. First I design by sketching, revising and figuring out dimensions and proportions before I begin building or modeling anything. After I am satisfied with my concepts, I may make a few models of different angles or any part of the piece that I can’t quite visualize on paper. After I have figured out most aspects of the piece, I began with the most challenging or the focal point of a piece. Next, I continue finishing the work similar to assembling furniture from instructions. Separating the two phases of working helps me focus in the studio and not second-guess myself. While I appreciate spontaneity and will often change aspects of the original design if looks stronger or I see something is not working, I stay on task better and work faster this way. I often work on multiple pieces at a time as it helps balance my load when I reach a point when I can’t continue on the same piece any further. Because I design instructions for myself, I do not have a difficult time knowing when it is finished. LAL: What kinds of research did you carry out for the conception of these works? KEA: I read as many books, articles and publications as I could find about sugar consumption, the history of production and how it is consumed. I also sketched and created models to help me visualize my thoughts. LAL: Anything surprising/interesting you learned from your research? KEA: Sugar was originally a delicacy so rare that royal families only purchased a few pounds at a time. Processed sugar is one of the first substances produced for Royalty that became a staple of peasant life as well. LAL: Both of the works have a very minimal and clean style. How does this aesthetic contribute to the work? Is this aesthetic typical for you? KEA: The aesthetic is meant to reflect modernity while still feeling inviting. I consider the dichotomy between, clean and simple design and disturbing quantities of sugar the focal points of the work. This stylization is inspired by processed food advertising, which uses similar tactics to entice consumers to overindulge. LAL: Proportion seems to play a role in these works (especially in that impressively huge glass jar!) Why was it important to you to manipulate scale and proportion? KEA: Manipulating scale allows to me to visually emphasize what I want my audience to see as most important. I wanted the jar to emphasize excess but also look like it could exist in a restaurant or some other contemporary eatery. The larger scale items draw attention from farther away and create striking outlines, while the smaller intricate pieces invite viewers in for introspection. LAL: Did you cast the serving utensils yourself? What made you choose bronze as the medium? Can you talk about the interesting shape of them? KEA: A team of artists including myself cast all of the bronze components. I chose bronze because of the traditional ties it has to sculpture in art history. Although serving ware is traditionally made from steel, bronze seems special, precious and a nice contrast to the wooden components. LAL: Both of the works contain found objects. What is your process for finding these objects? Do you have something very specific in mind? Do you ever manipulate the object to achieve the aesthetic you want? KEA: My process for finding objects so far has been pure luck. Self-service started by finding the jar in the University foundry yard and designing the first draft of the work in my head as I studied its shape. I have used kitchen tables as pedestals before and the association with food, ritual and tradition enhance my concepts. I will do minor alterations to found objects but anything major is probably not worth my time to modify. It would be better just to redesign something using the found object as a reference than to manipulate it. LAL: The show at LAL is titled FEAST: Pleasure + Hunger + Ritual – If you could put Pile and Self Service in one of these categories (pleasure, hunger, or ritual) which would it be and why? KEA: I would place both works under the Title of Ritual. As a country, we ingest more sugar a day now than any other period of history and this has been a gradual shift. Dessert, soda, coffee, candy, and sugary confections of all sorts are inseparable from our modern life and are consumed in many ritualistic avenues. LAL: What is the one thing you hope for people to take away from viewing these pieces? KEA: To think about what they are eating, and what it contains. Raising questions from my audience is more important that answering any. Lexington-based artist Melissa Shelton manipulates and exploits her subject matter to transform it from humble food to consumer culture critique. Her seven-foot-tall painting Inveiglement dominates the space and demands attention, forcing the viewer to confront their own perceptions of food, consumption, and desire. Utilizing scale, sophisticated color handling, and texture, the piece manages to occupy a delicate space between seduction and repulsion. Currently a B.F.A candidate at The University of Kentucky, Shelton employs the symbolic images of fruit in culture to investigate sexuality and sensuality. Having already earned a B.A. in Integrated Strategic Communications, Shelton has explored and been inspired by advertisement strategies and the psychology behind media manipulation, especially those surrounding female standards of beauty.

We contacted Shelton to learn more about her piece Inveiglement currently on display here at Lexington Art League. Lexington Art League (LAL): What does “inveiglement” mean and why did you choose this title? Melissa Shelton: Inveiglement means to draw in, to entice and capture. I would like the viewers to take their own meaning from that. LAL: Your artist statement says that you are exploring relationships between beauty, body, and food, especially how media portrays beauty. Why are you interested in these topics? MS: I think these subjects have so much meaning and are so deeply complicated and intertwined in our culture today. Growing up in my family, you showed someone you loved them by making them food. And I have always loved food, but I never loved my body. I can’t say I know many women who haven’t had body image issues. I knew girls in middle school, girls wearing training bras and glitter lip gloss, that dieted. After studying those strategies that ingrained those unrealistic expectations I was hurt and angry. LAL: What made you choose fruit to represent these themes? Any specific references to fruit in culture that inspired you? MS: Well, I am also Catholic. Eve and the apple was my first entrance into fruit as representative for the female body. Eve’s guilt and shame speaks to these themes as well. Fruit has this sexy but dark culture surrounding it from Snow White to Persephone’s pomegranate seeds. And women are somehow always at the center of the story. LAL: How do you manipulate the aesthetic so that the piece goes beyond a still life? MS: Abstraction and stylization. The texture and movement is what I particularly like to focus on to create a more visceral reaction than a still life would have typically. Also, ambiguity. I like to let it be more than one “thing” at a time, an orange, grapefruit, flower, even musculature. LAL: How do you research when you are about to begin a new painting? What types of things did you look at specifically for Inveiglement? MS: I like to spend a lot of time with my subjects. I ate a lot of blood oranges, pink grapefruits and clementines stolen from the fiber studio. I picked and peeled them apart, used a magnifying glass, a knife and camera, watched them rot even. After that I saw them very differently. I started looking at muscles under the skin, pruney fingertips, and raw meat. LAL: Any artists that inspire you? What about their work inspires you? MS: Marilyn Minter is my hero. She’s not afraid to be gross and disgusting and that becomes sexy. I could watch her caviar video series all day. Jenny Saville is that way also in her paint handling, really vulgar and beautiful at the same time. LAL: Speaking specifically about Inveiglement what was the inspiration and concept behind it? MS: I picked up a bag of blood oranges on sale at Wal-Mart for some fresh orange juice. As I sliced it in half, its dark pink almost wine colored juice seeped onto the counter. I pressed and pinched and squeezed that fruit of everything it had left and drank its last drop, a little bitter but still sweet. I stared at its carcass and all its siblings left in the bag and that was that. This piece is part of a larger body of work exploring the same themes through different subject matter, different pieces of fruit. LAL: I think the work has the interesting ability to capture beauty and yet make the viewer uncomfortable at the same time. What (typically) are people’s reactions to this work? What kind of reaction are you hoping for? MS: People are usually not sure what it even is. It’s not every day that you get to see something that fits in your hand at a larger scale than you are. I hope that the viewer first spends some time with the work, to let it seduce you, let it disgust you, to just look and try to find meaning in that. LAL: The show at LAL is titled Feast: Pleasure+ Hunger + Ritual. If you could put Inveiglement under one category (pleasure, hunger, or ritual) which would it be and why? MS: Hunger. I think Inveiglement hungers for some attention. To hunger for something or someone is THE most primal instinct we have. And if I can leave the viewer a little hungry, that’s all I can ask. LAL: What is the one thing you would want viewers to take away from Inveiglement? MS: Really, I want my viewers to examine their desires and their hunger. What is good enough for you to eat? LAL: What advice would you give to new artists or undergrads pursuing an art major? MS: Don’t limit yourself. What you’re feeling is valid so follow your instincts. Poke and prod around until you find what you love and make it your life. See more of Shelton's work on her website http://www.melissa-shelton.com/Info.html Inveiglement by Melissa Shelton |

Archives

March 2021

|

|

Public Gallery Hours

Wednesday 12pm-5pm

Thursday 12pm-5pm Friday 12pm-5pm Saturday 12pm - 5pm Viewings also available by appointment |

The Loudoun House

209 Castlewood Dr. Lexington, Ky. 40505 Email: [email protected]

Phone 859-254-7024 |

|

All Lexington Art League programs are made possible through the generous support of LexArts.

|

The Kentucky Arts Council, a state arts agency, provides operating support to the Lexington Art League with state tax dollars and federal funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support provided by Lexington Parks & Recreation.

|